The PA27Q is a gaming display, not one that’s specifically intended for high-end photo editing or graphic design. It’s only rated to 300 cd/m2 brightness by Asus, which isn’t as high as some displays, but we must stress that this wasn’t a problem in use, and it never appeared dull or washed out. With the brightness turned up, the screen looks vivid and colourful, and most importantly, games look really good on it.

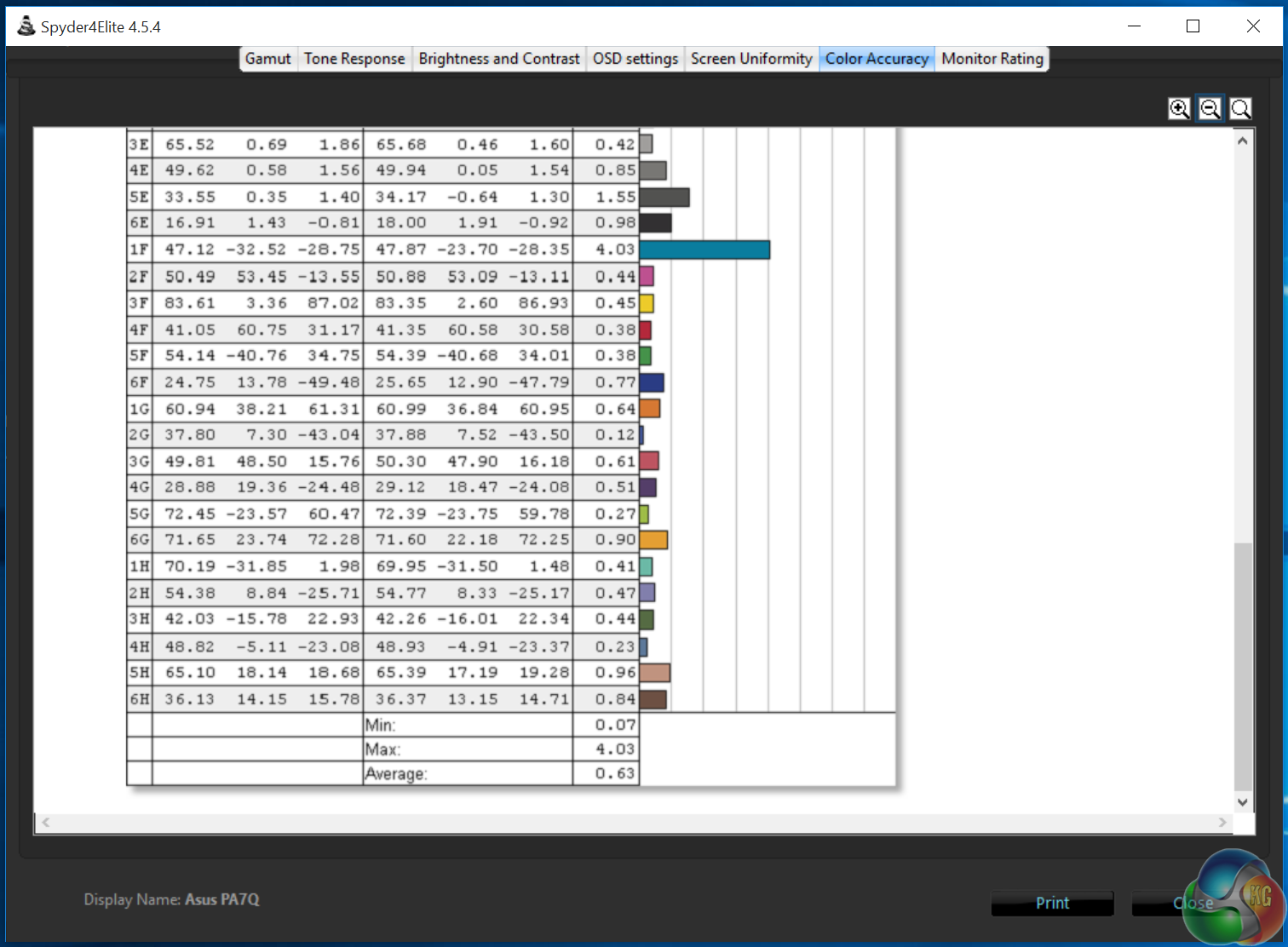

We used a Spyder 4 Elite Colorimeter to measure the colour accuracy of the PA27Q, as we do with all displays. We reset the screen to factory defaults, to measure its out-of-the-box performance, then we calibrated it and measured its colour accuracy afterwards.

Calibration was set to 120cd/m2 and we also tested all the presets, since there are quite a few on offer.

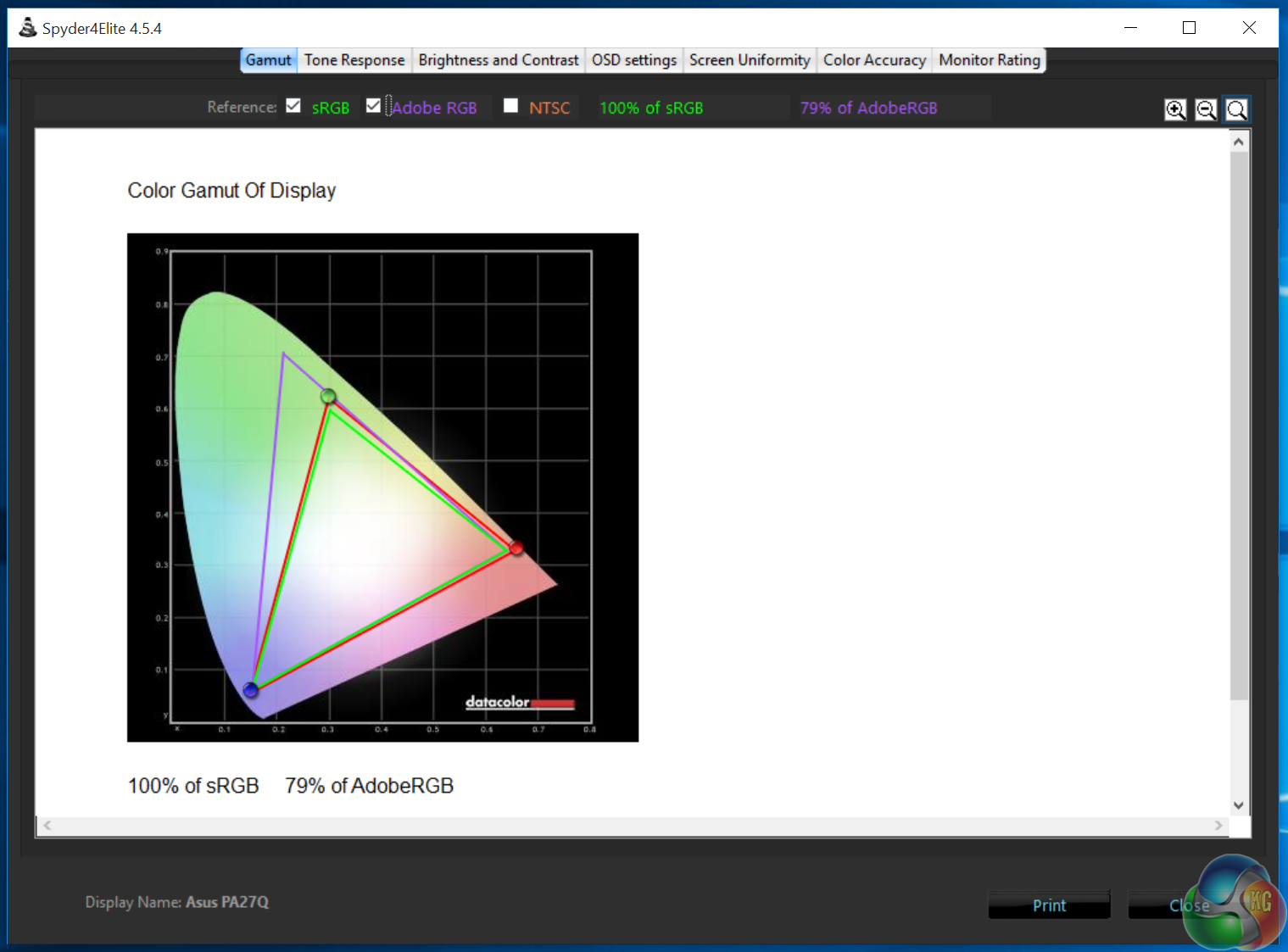

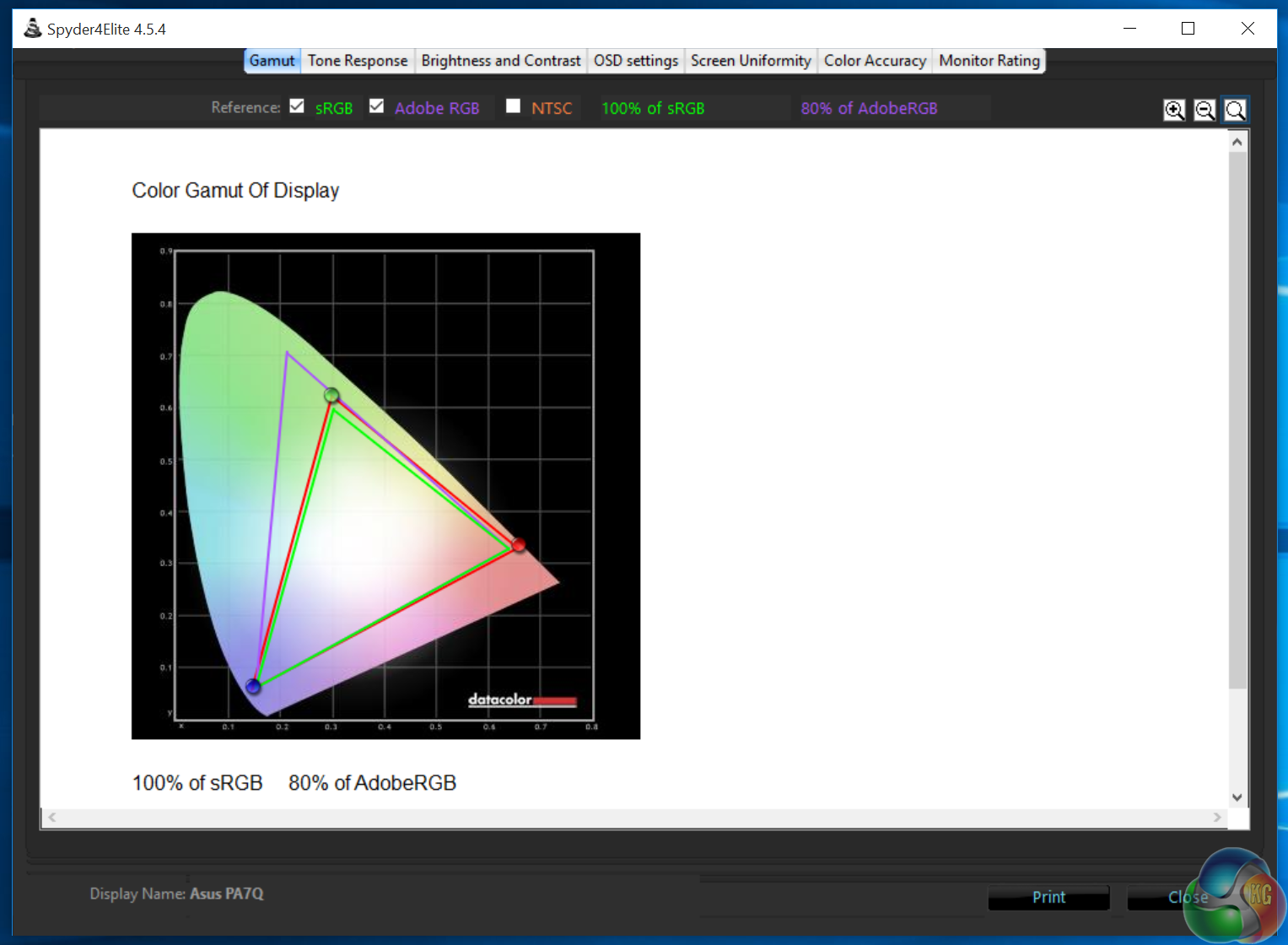

We now expect close to 100 per cent sRGB coverage from every screen we test these days, and that’s exactly what we get here, with 79 per cent Adobe RGB. Panels are really good these days, and for better results, 99 per cent Adobe RGB coverage is possible only with high-end displays aimed at graphic design work.

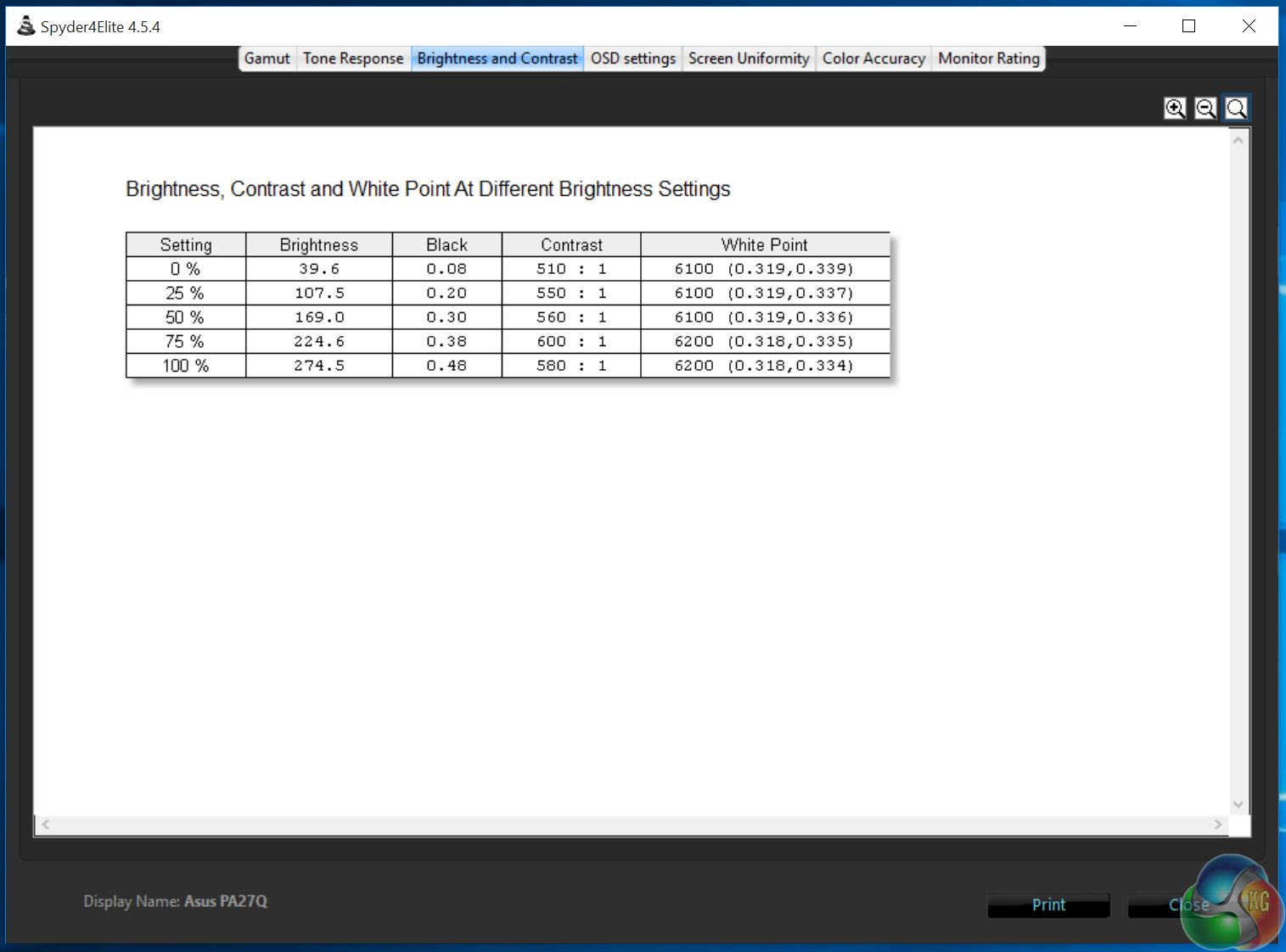

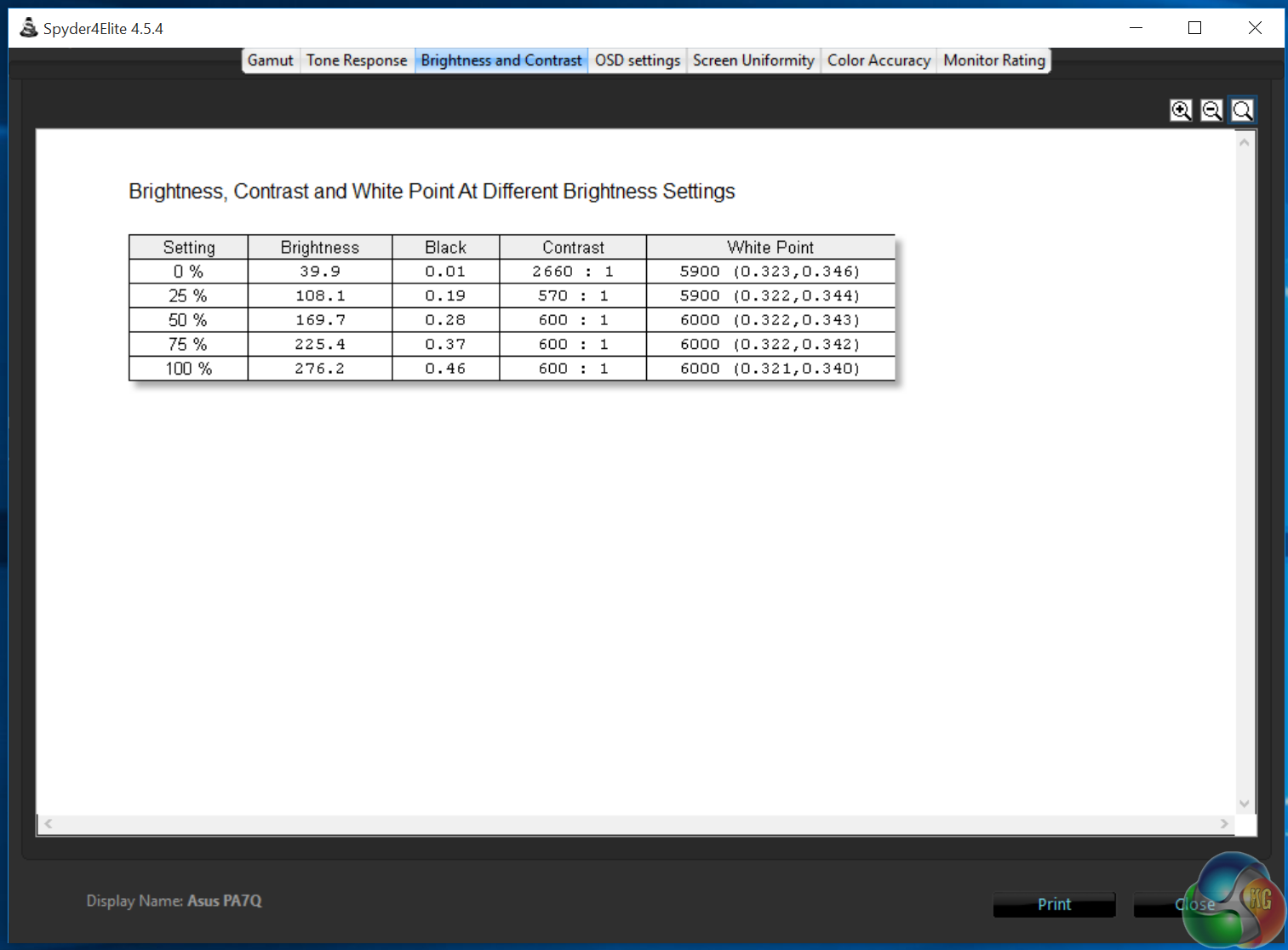

The measured brightness comes out slightly lower than Asus’ 300 cd/m2 figure, but after using the screen for a while, although the PG27AQ isn’t capable of retina-burning brightness, it does not appear dull or washed out in any way. We spent a lot of time testing it with various images, web pages and playing games.

The 550:1 contrast levels are noticeably spectacular though, with some very deep blacks that enhance dark areas in games. The white point is at 6200K, while the black point is 0.48, fairly average for a gaming display.

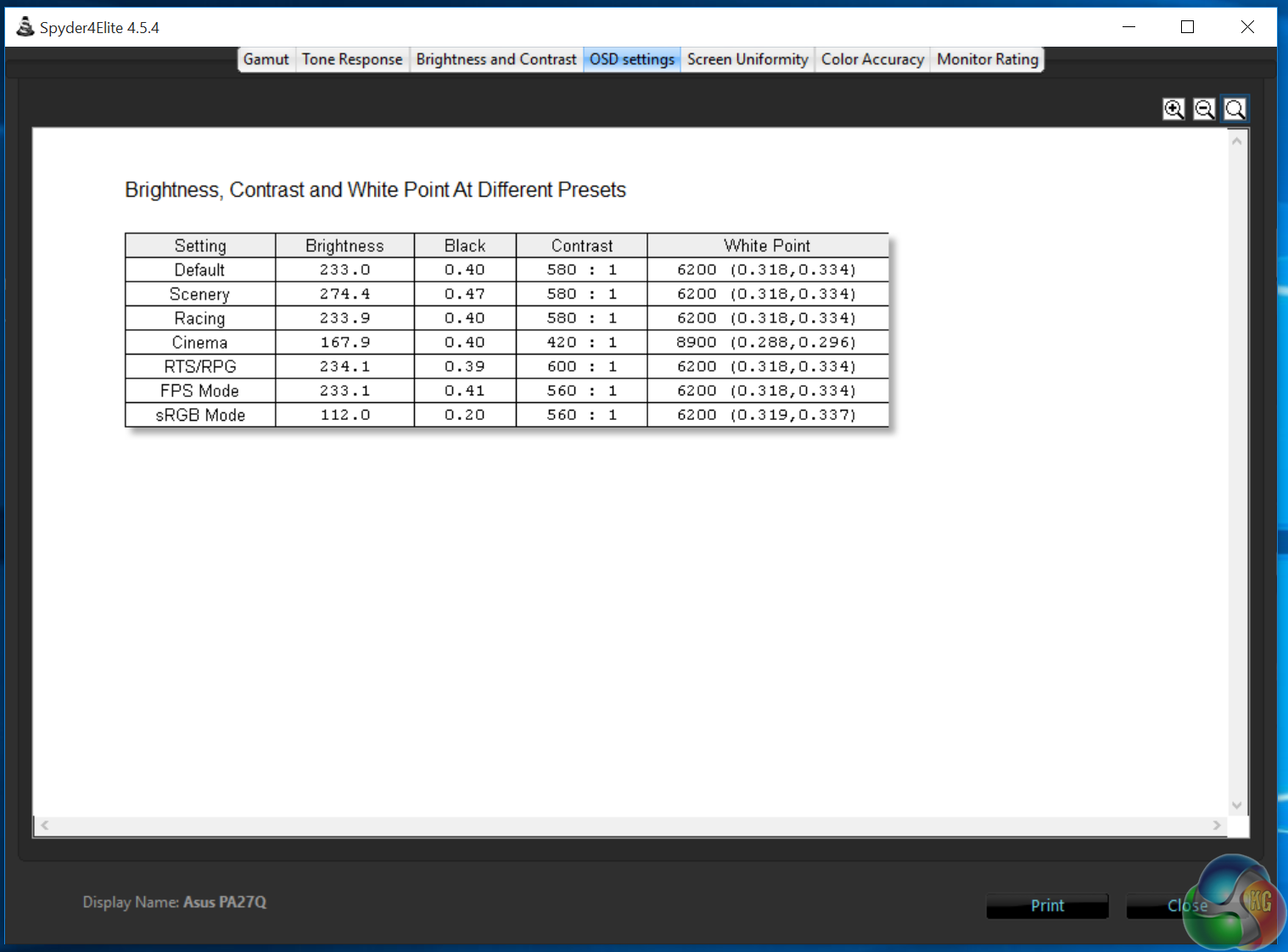

The GameVisual OSD presets show a lot of variation. The sRGB mode does darken the screen a bit, and the RTS mode looks very good.

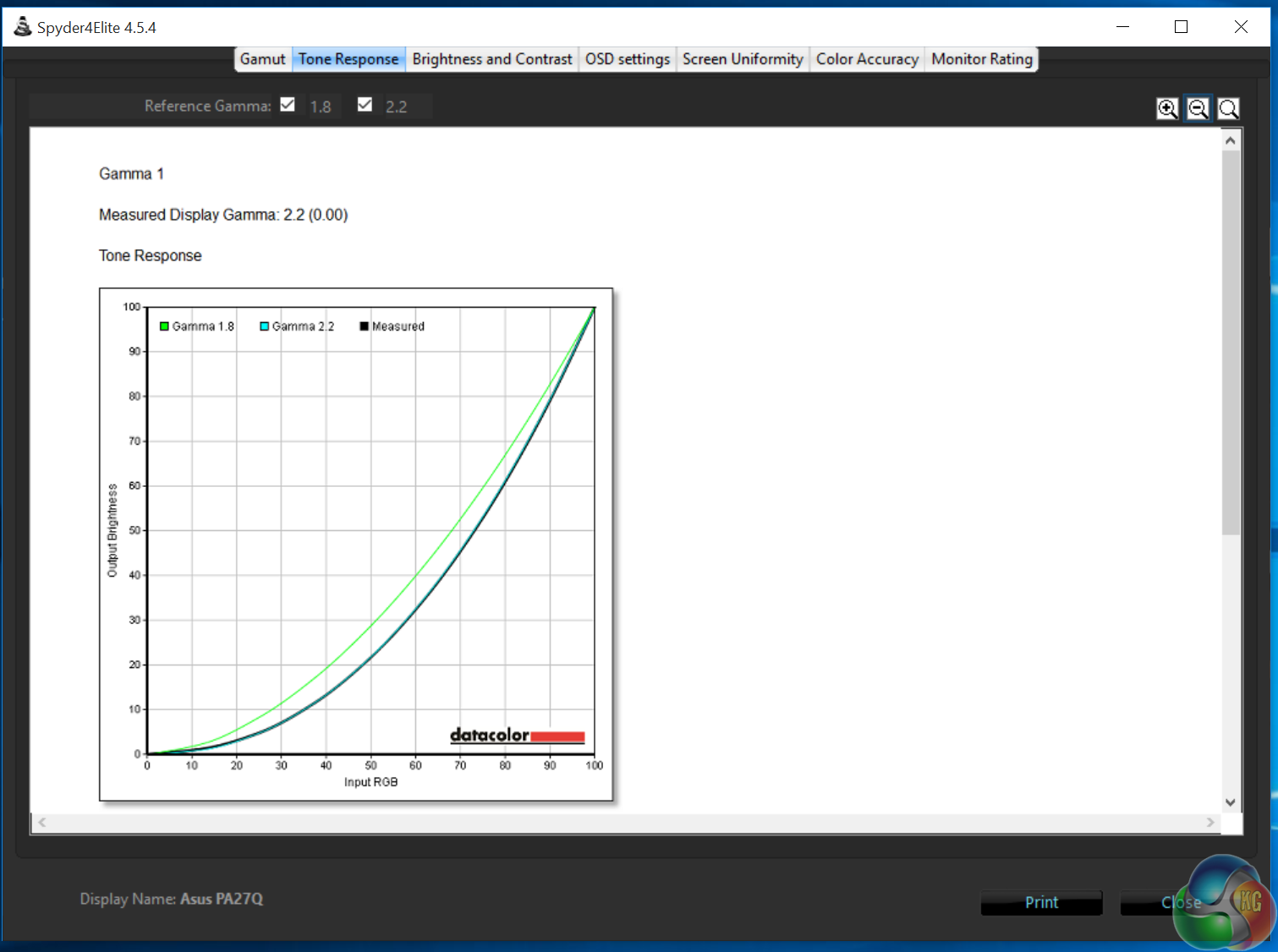

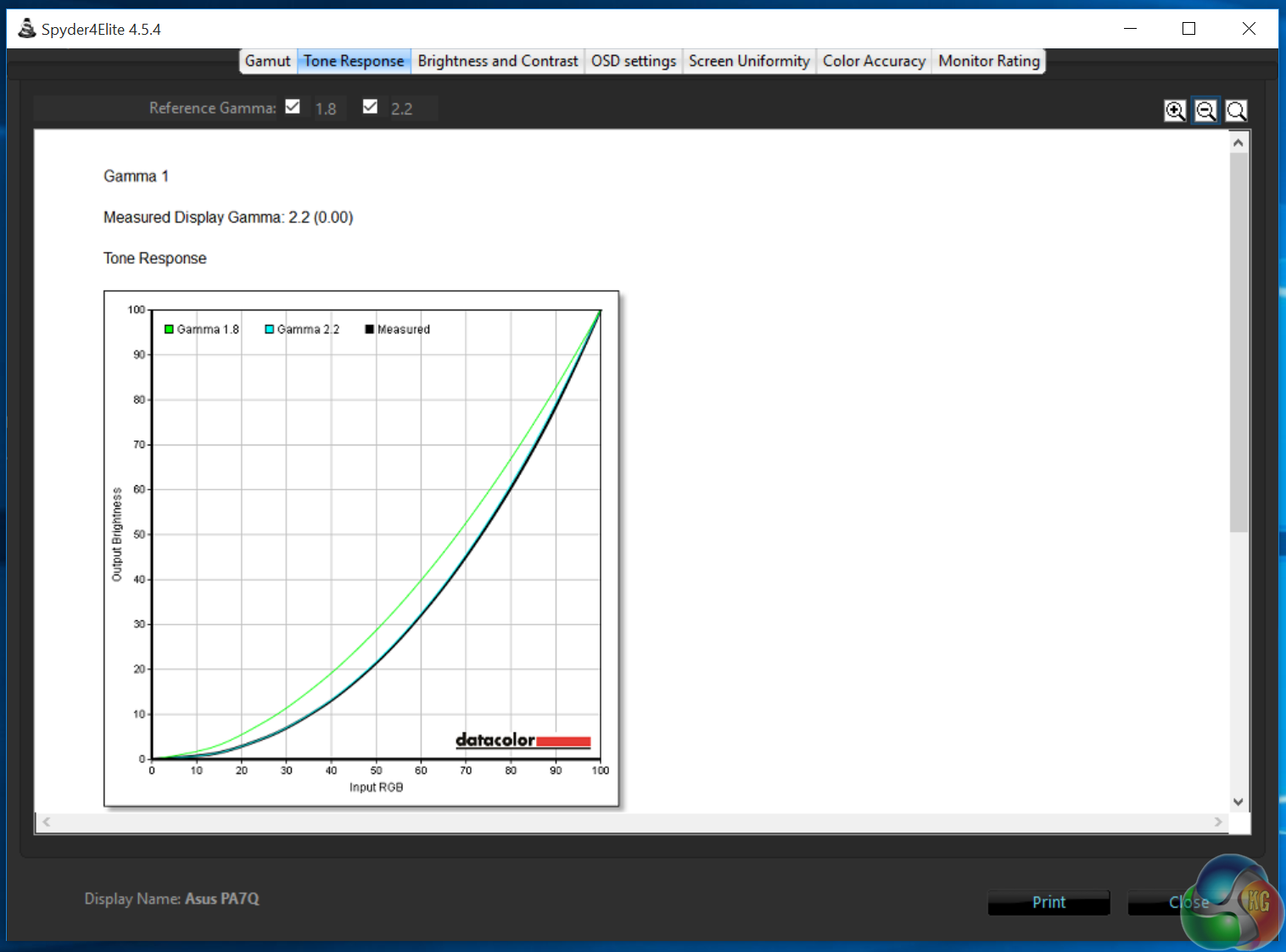

The default gamma, which cannot be adjusted, is bang on 2.2

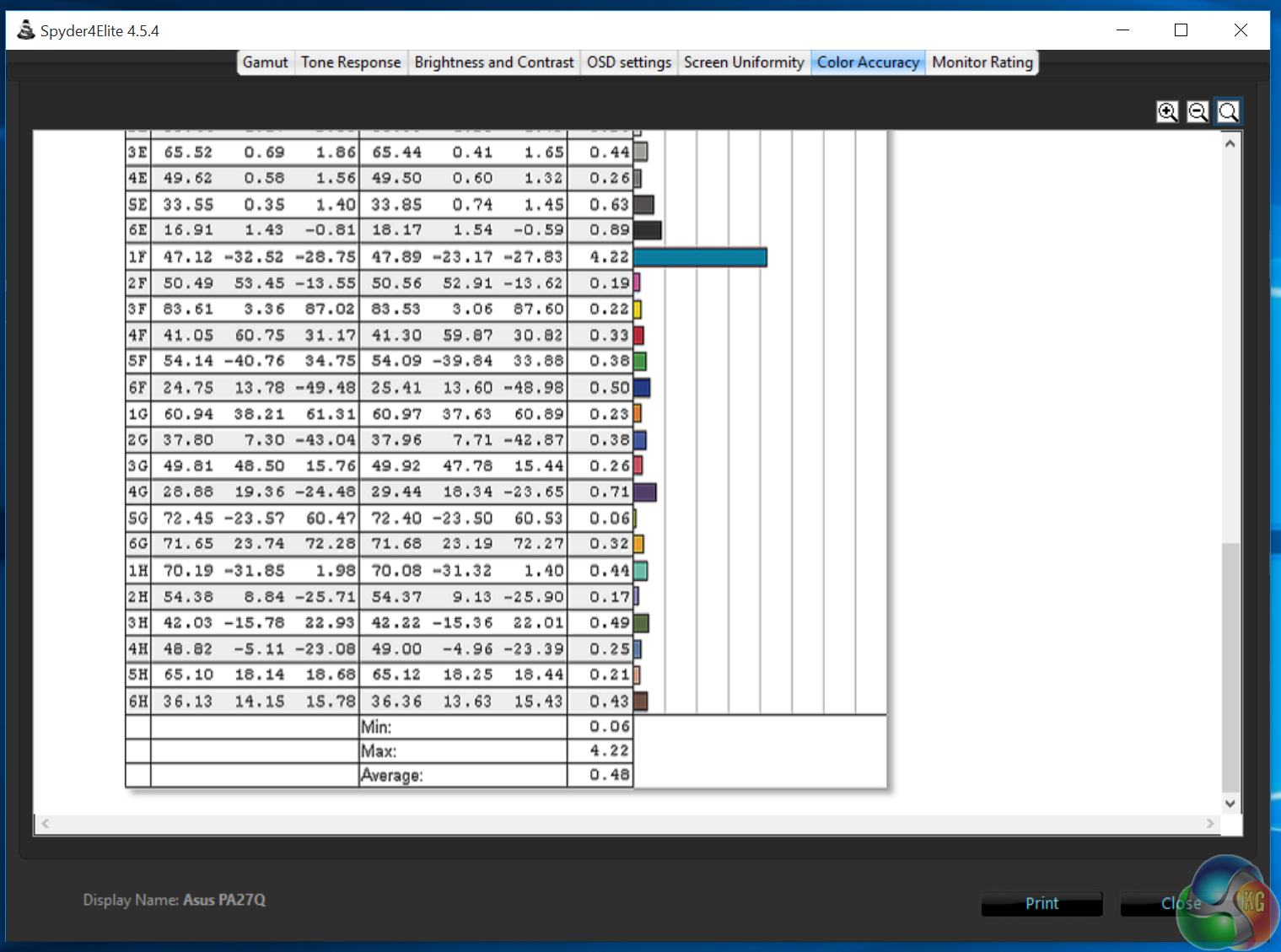

And lastly, we get a colour accuracy result with a Delta E under 1, superb for a gaming display.

The brightness uniformity is all over the place with a gradual shift in brightness from the top to the bottom of the screen. It would be a serious concern in a display aimed at graphic designers, but this is perfectly acceptable here. And really, isn’t at all noticeable.

Once we’d calibrated the screen, the Adobe RGB increased slightly to 80 per cent coverage.

Brightness and contrast are roughly the same

As is the gamma level.

The colour accuracy remains under 1, although notably increases slightly over the factory configuration, although this is such a small difference it could be explain as with the margin of error.

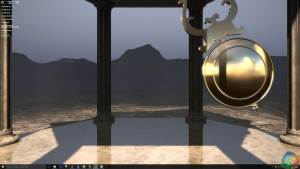

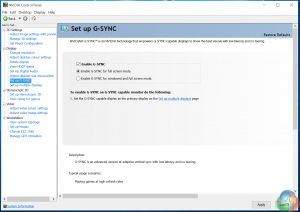

Of course, we also tested the PG27AQ with 3D applications and games to see how well its G-Sync feature worked. The first way is with Nvidia’s Pendulum demo, a scene with a pendulum swinging. With G-Sync disabled, its motion causes severe screen tearing, but this glitch goes away when G-Sync is turned on. And with the PG27AQ this effect was very noticeable and worked well.

We also had a go with Battlefield 4, still a relatively modern and demanding game. What’s notable is that, even on a GeForce GTX 970, for a solid frame rate at 4K resolution that never dropped below 60fps, we had to reduce the game’s detail settings to medium, with it dropping below 60fps at ‘High’ detail in some of the more busy scenes.

With G-Sync turned on, gameplay with medium detail settings in Battlefield 4 was fast and fluid at 4K, as expected, with no screen tearing or jitter.

We ran into a small technical issue with the PG27AQ. Switching between HDMI and DisplayPort would occasionally cause the buttons to stop responding to presses. Every time it happened it was right after we had used an HDMI device. This could be just a glitch with our review sample though, and possibly connected to the HDMI Deep Sleep setting in the OSD.

Lastly, we measured the power consumption, which we expected to be higher than a standard 1080p display, given the higher number of pixels to illuminate. The reading was 47.7 watts, more than most displays but not particularly high for a 4K screen.

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards

For 4K @ 144Hz, they can just add second DP 1.2, similar to 5K displays. Could be more future proof, as most cards have multiple DP outputs.

The initial 4K displays used multiple displays inputs and that didn’t work well at all. Loads of problems with tearing and such.

Wasn’t that because the displays were set up to treat the 4K screen as two separate “halves”?

Yeah, and that’s what you’d have to do with TristanSDX’s solution.

Weren’t the early panels physically 2 panels though? I seem to recall hearing that the split wasn’t just logical, that a single 4K panel was too expensive to make back then so two cheaper 1920*2160 panels were stuck together in a single frame to make it work.

Why couldn’t the bandwidth provided by the 2 DP cables be aggregated without having to virtually split the screen into two halves?

Leo should have done a video review of this.

Any way to get this in the USA yet???

You can get it now at Newegg. And some time soon Amazon will have it in stock.

You say that gsync effect is striking at 144hz and less so at 60hz? 144hz does not and never has needed adaptive sync to make it impressive. I really wonder if some of the people singing gsync praises had ever used a high refresh monitor before they tested gsync. All the explanations of the benefits gsync has at 120hz and above are actually the benefits of 120hz and above.