AMD continues to chip away at Intel’s market share in the server segment that Team Blue has dominated for most of the previous decade. The recipe for this rise in AMD market share has been the EPYC 7002 Series ‘Rome’ processors. Those Zen 2-based datacentre chips offer higher performance at lower costs in many workloads when compared to Intel’s competing Xeon offerings.

Even on heavily multi-threaded processors intended for servers and datacentre operators, maximum CPU clock speed remains an important metric. It is an area where many of Intel’s Cascade Lake Xeon parts offer an advantage versus their AMD competitors.

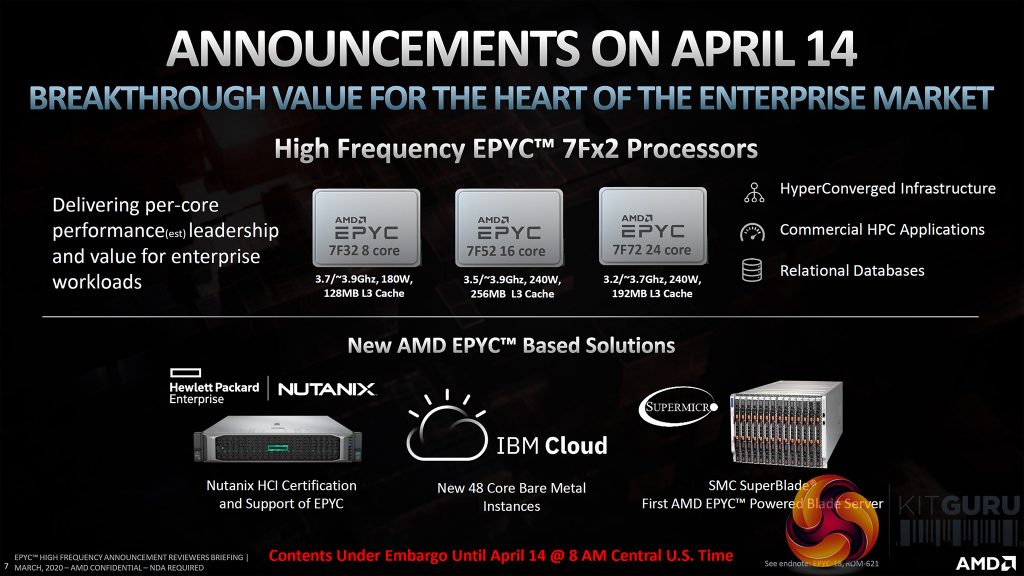

AMD is keen to bring new guns to the clock speed fight with a trio of TDP-boosted EPYC 7Fx2 series processors. There is the 8-core EPYC 7F32, 16-core 7F52, and 24-core 7F72.

The first noteworthy point for each of these processors is the significant TDP bump versus its ‘standard’ EPYC 7002 series siblings and the enhanced clock speeds those bumps bring about. But there are also variations in the cache capacity of these chips compared to their siblings. Oh, and of course, prices have been increased by significant amounts.

Examples where maximum frequencies on lower core counts chips are desirable can be in database tasks, high-frequency trading, research and development projects with specific software, etc.. If the specific program is old (typically end-of-life for updates), poorly coded (by modern standards), and has limited ability to scale with extreme core counts, yet still requires large amounts of cache and significant RAM bandwidth, the 7Fx2 parts could be candidate processors.

Similar examples of cloud-centric workloads will undoubtedly exist. And that’s before even mentioning the benefits of higher clock speeds and lower core counts for performance in software that is licensed on a per-core basis.

Of course, the research task being undertaken or the database being managed needs to be important enough to justify the required price increase versus the ‘standard’ EPYC parts. But when looking at Intel’s recently released high-frequency Xeon ‘R’ competitors, AMD’s lofty price points start to become understandable (that’s not to say justifiable).

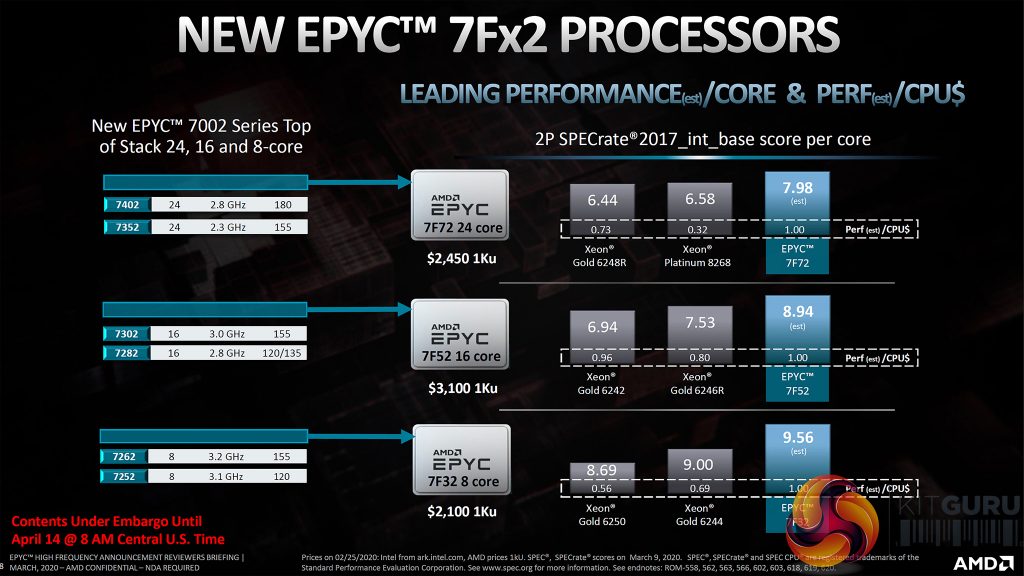

Let’s focus first on the 8-core EPYC 7F32 compared to its 7252 and 7262 siblings.

We see a TDP increase from 120W for the 7252 and 155W for the 7262, to 180W for the 7F32. That adjustment in TDP increases the maximum boost frequency from 3.2GHz and 3.4GHz, respectively, to around 3.9GHz for the new part. The base clock speed is also increased from 3.10GHz and 3.20GHz up to 3.7GHz, which is certainly pretty slick by server chip standards even for an 8-core part.

Another of the key points for the 7F32 processor is its 128MB L3 cache capacity that is the same as the 7262 but double that of the 7252. In essence, the new 7F32 looks to be a higher clocked 7262. That comes with a significant price premium, according to AMD’s data. The new 7F32 8-core chip is suggested to sell for $2,100 1000-unit pricing whereas the older and slower 7262 is currently less than £600 in the UK and around $600 in the US for single-unit retail pricing.

Clearly, the 7F32 is designed for environments whereby eight cores with a large slice of L3 cache make a perfect fundamental combination and the need for high clock frequency is worth the significant price premium to prospective users.

If you’re working on a £500,000 engineering project with software that only leverages and licenses up to eight-cores (which is absolutely not uncommon), spending a disproportionately higher amount for the frequency bump of the 7F32 processor is perhaps justifiable for the time savings it can provide.

The AMD EPYC 7F52 is a 16-core, dual-socket-capable part and therefore slots in alongside the 7282 and 7302 in AMD’s line-up.

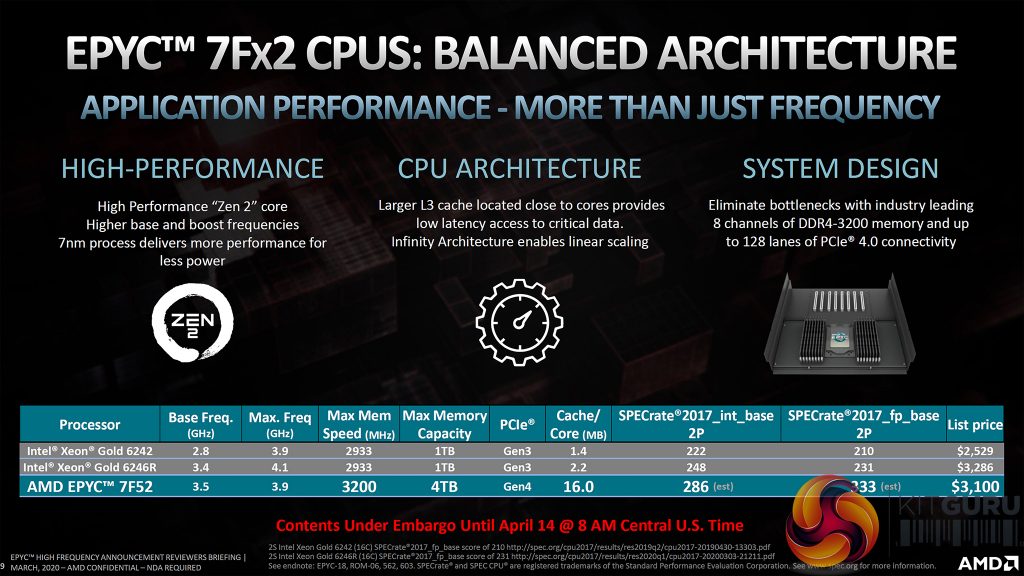

Looking closer, we see that the 7F52 is realistically a 7302 with double the L3 cache and higher base and boost clocks thanks to the increased TDP. The 16-core 7302 offers a base clock of 3.0GHz and maximum boost clock of 3.3GHz with a 155W TDP. By comparison, the new 7F52 comes in at 3.5GHz base, 3.9GHz maximum boost and uses a TDP of a gargantuan 240W.

Clearly, with a 240W TDP and 1ku tray pricing of $3,100 versus the 7302’s roughly-$1000 availability, the new 7Fx2 16-core part is for a niche audience. That audience is likely to consist of users with applications that will benefit from the doubling of L3 cache capacity to 256MB.

Workloads that sit happily within 16 cores but scale well with frequency and cache capacity would make logical sense for partnering with the 7F52. The real competitor, in that case, is Intel’s recently released $3,286 Xeon Gold 6246R with its 3.4GHz base and 4.10GHz maximum boost clock. Cache capacity and memory support are clearly in favour of AMD’s chip in that fight, but it highlights the competition that AMD is gunning for from Intel.

Leading the line (somewhat) for the new 7Fx2 series processors is the 24-core 7F72. This dual-socket-capable chip sits alongside the EPYC 7352 and 7402 processors that are currently available.

With its gargantuan 240W TDP, the 7F72 provides a base clock of 3.2GHz and a maximum boost speed of 3.7GHz. That’s compared to the 180W TDP 7402 and its 2.80/3.35GHz clocks. Also different with the 7F72 is its larger serving of L3 cache at 192MB versus the alternative 24-core chips’ 128MB.

At $2,450, 1ku pricing for the 24-core 7F72 is actually cheaper than the 7F52 and close to that of the 8-core 7F32. We were initially surprised by this but had it confirmed by AMD.

The pricing designation of each chip provides us with some interesting suggestions for the topology. The 16-core 7F52 and its $3,100 price tag looks to be an outcome from the full eight-CCD configuration used by the chip. We make this assumption based on the 256MB cache capacity that would require the L3 cache from eight Zen 2 CCDs. That serves as some type of explanation for the pricing structure, alongside the high frequencies on the lower core-count chips that suggests significant chiplet binning.

Another obvious justification for the pricing of AMD’s 7Fx2 parts is that Intel’s recently released Xeon ‘Performance’ competitors are far from cheap. While AMD is clearly still in the game of winning market share from Intel, the chip vendor’s Zen 2-based EPYC processors have proven to be viable solutions. That puts AMD in a position whereby the company perhaps does not feel that price advantages versus Intel are necessary as its parts can compete in terms CPU performance, memory support, and platform interconnectivity.

All of the conventional benefits of EPYC 7002 Series ‘Rome’ processors are retained with these new 7Fx2 parts; you get 128 PCIe Gen 4 lanes per chip, 8-channel memory support with up to 3200MHz clock speed and 4TB capacity, and they slot into SP3 socket motherboards with single- or dual-CPU operation potential (though motherboard support is likely to be heavily dependent upon power delivery and cooling capabilities).

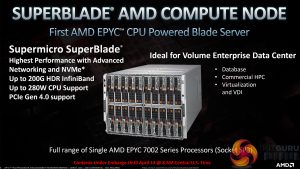

AMD highlights that the new higher-clocked parts will be available in servers from the likes of Dell, Supermicro, and Hewlett-Packard Enterprise from April 14th 2020.

KitGuru Says: AMD is clearly aiming to fight Intel in every segment of the server and datacentre market. High-frequency offerings remained an area of strength for Intel even in light of AMD’s EPYC ‘Rome’ competitors. Intel furthered its high frequency offerings in February with the Cascade Lake Xeon ‘Performance’ CPUs and now we see AMD’s reaction. What are your thoughts on the EPYC 7Fx2 series options?

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards

KitGuru KitGuru.net – Tech News | Hardware News | Hardware Reviews | IOS | Mobile | Gaming | Graphics Cards